- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Only seven years after their resplendent pioneering exhibition and catalogue on the seventeenth-century Japanese artist Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558–1637), Felice Fischer, Kyoko Kinoshita, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art produced an even more magnificent catalogue and exhibition on the artists Ike (also known as Ikeno and Ike no) Taiga (1723–76) and Tokuyama Gyokuran (1727/28–1784). Like Kōetsu, who was himself a calligrapher, potter, and lacquer-ware artist, Gyokuran and her husband Taiga were stylistic and social pioneers who worked in several arts, in their case painting, calligraphy, poetry, and even seal-carving and lacquer, in the style called Nanga.

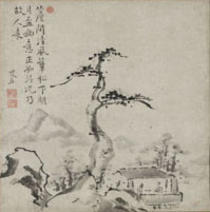

One of several new styles that emerged and flourished in Edo period Japan (1603–1868), Nanga was inspired by Chinese literati ideals and derived from Chinese literati sources. Nanga, literally “Southern School painting” (also known as Bunjinga), like its antecedent, the Chinese wen-jen hua, or “literati painting,” integrated the study of painting, calligraphy, poetry, Chinese classics, connoisseurship, and tea and other arts. The ideals are expressed both in the “calligraphic” line (of painting as well as calligraphy per se) and the vocabulary of strokes, in countless stylistic subtleties such as color usage, and in subject matter. Cherished themes are plants symbolizing the virtuous qualities of the ideal gentleman (pine, bamboo, chrysanthemums, orchids, and plums), and landscape—both anonymous and named scenes derived from literature and history with titles such as The Peach Blossom Spring, The Red Cliff, The Journey to Shu, and the Lan Ting (Orchid) Pavilion. All these subjects were favorites of Gyokuran and Taiga.

Taiga, the most important—and prolific—artist of the Nanga style, produced over a thousand documented paintings and calligraphies over the course of a career that began in early childhood. Gyokuran, his wife, is arguably the most important woman artist prior to the twentieth century; she was much admired (and forged) during her lifetime and afterwards. (Indeed her paintings, Kinoshita informs us, probably cost more than Taiga’s at times.) Both artists were accomplished poets as well; Gyokuran was the third generation in a female line of poets whose work was published during their lifetimes.

One of the major accomplishments of the exhibition and its catalogue is the inclusion of enough examples to provide an appreciation of both Taiga’s and Gyokuran’s artistic development and the range of their stylistic temperaments. In both cases their range is wide enough to make connoisseurship a real challenge, so the numerous examples of the various themes by each artist are especially welcome for the comparisons they facilitate. The exhibition and catalogue also include a number of one-of-a-kind works: Gyokuran’s Banana and Grapes from the famous six-fold-screen called Plants, and Taiga’s famous travel diary and sketch book, Journey to the Three Peaks, now mounted on folding screens, among other important works.

The exhibition, organized by the Philadelphia Museum of Art with the special cooperation of the Tokyo National Museum and the Osaka Municipal Museum of Art, was the first major exhibit of Nanga/Bunjinga works in the United States in recent years, the first on Taiga and Gyokuran, and the first in the world to show their work on such a scale: 208 works (over 420 counting as separate works those album leaves and screen panels that have separate compositions), over half from Japanese collections. A third are by Gyokuran, and their display permitted detailed comparison of the two artists who worked so closely together. There are a number of collaborations between the two artists represented, as well as examples of Taiga’s pedagogical works. A major rotation halfway through the exhibition schedule offered an opportunity to see an expanded number of works while protecting works whose media (silk and paper) make them fragile.

The six sections of the exhibition, reflected in the organization of plates in the catalogue but not in the essays, focused on 1) Taiga’s dated works (1733–1749), chronologically illustrating the artist’s stylistic development; 2) Chinese themes, such as reclusion and bamboo painting; 3) calligraphy; 4) Japanese themes; 5) the artists’ Chinese landscapes, and 6) the late works, reflecting Taiga’s culminating stylistic synthesis. They include every format: screens, handscrolls, hanging scrolls, fans, and albums.

Taiga’s output is singularly impressive for its range of styles, techniques, compositions, and subject matter. Most of these styles were represented in the exhibition, including his “flung ink,” several finger paintings (a new style imported to Japan from China), and “flying white” bamboo (analyzed in Sadako Ohki’s chapter on his bamboo paintings with calligraphy). As Melinda Takeuchi showed in her book Taiga’s True Views: The Language of Landscape Painting in Eighteenth-Century Japan (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1992), Taiga discovered new ways of seeing and understanding landscape, inventing a style scholars came to call shinkeizu (“true-view” pictures) that ushered in the utilization of empirical methods and the celebration of the individual artist’s spirit, both of which were essential to later modernization. Several examples of Taiga’s “true-views” were included in the exhibition, including the “bird’s eye” view True View of Mt. Asama; True View of Kojima Bay, one of his most famous works; and the Wondrous Scenery of Mutzu, representing Taiga’s memories of his first journey to Edo in 1748. Equally remarkable is Taiga’s 1771 album of fan paintings and calligraphies of the Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers. A favorite theme of Chinese and then Japanese literati, these views can become almost formulaic. But Taiga’s radical stylistic departure is, in two of these fan paintings especially, so minimalist as to be almost abstract. Other exceptional works included two Japanese national treasures, shown outside Japan for the first time: the Tokyo National Museum’s pair of six-panel screens Landscape with Pavilions, and the well-loved but rarely seen Ten Conveniences, a set of ten album paintings (formerly in the collection of Nobel Prize laureate Yasunari Kawabata and now owned by the Kawabata Foundation) that were made as companions to the Ten Pleasures by fellow literatus Yosa Buson. Nanga was an unusually sociable art, in which friendships and collaborations played not only a practical role (as it did in ukiyo-e printmaking) but intellectual, social, and artistic roles as well. Other collaborations shown included the Essay on Fulfilling One’s Desire, a handscroll landscape of 1750, on which Yanagisawa Kien—Taiga and Gyokuran’s painting teacher—wrote the title, and Gion Nankai, another highly respected bunjin and painter, wrote the Chinese text. Several examples of Taiga’s paintings that were done as works with, or as models for, his wife were also included in the exhibition. Taiga’s self-portrait with his patron Mikami Kōken is one of the earliest Japanese self-portraits, and is unique in showing Taiga meeting with a patron.

The exhibition also offered unparalleled opportunities to view works together that have been separated into different collections: Bamboo and Calligraphy, a pair of six-fold screens split between Japanese and U.S. collections, and eight of the twelve scenes of the Landscapes in the Four Seasons, likewise separated. Also on view was Five Hundred Arhats, a set of eight fusuma-e now mounted as hanging scrolls, also shown outside Japan for the first time.

Gyokuran’s wide stylistic range is also evident in the exhibition and catalogue, including relatively rare landscapes with figures and paintings on silk, works with pooled ink and tsuketate (gradation of ink within one stroke) brush techniques, works in vivid color (Spring Landscape), as well as the more typical (for Nanga) works in pure black-and-white or ink with light color, and in formats varying from fan paintings to hanging scrolls and handscrolls to fusuma-e (the wide, paper sliding doors that separate interior rooms). Especially precious among Gyokuran’s works are the rarely seen set of fusuma-e from Konkai Kōmyōji (in Kyoto) depicting West Lake, her only known work on this scale. A number of her Chinese-themed landscapes, such as Song of Spring and Luoyang Avenue, are among her most complex compositions. Her collaborative works shown include those with inscriptions by her mother, the poet Yuri (Orchid and Plum Blossoms), and Sages Playing Go under Pines, inscribed by Monchū Jōfuku, the head of Mampuikuji, the Obaku Zen temple at Uji. Since Gyokuran did not date her work, a chronology of her oeuvre depends on inscriptions by others (most commonly her husband) or must be reconstructed from historical information, such as the date of the Konkai Kōmyōji fire, or biographical information related to the colophon-writer rather than to Gyokuran herself.

Unlike many catalogues that merely reiterate the terms of the exhibition, Ike Taiga and Tokuyama Gyokuran: Japanese Masters of the Brush complemented rather than repeated the exhibition’s divisions. Production values are exceptionally high, and the scholarship cutting-edge—while also providing illuminating explanations thorough enough to bring nonspecialists into the fold. Fischer, the Luther W. Brady Curator of Japanese Art and Curator of East Asian Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and Kinoshita, Associate Curator of East Asian Art (who also assisted with the Koetsu catalogue), provide updated biographies as well as critical overviews of both artists.

These artists’ biographies are rounded out by additional chapters on special topics. Hiroyuki Shimatani’s contribution, “The Fascination of Taiga’s Calligraphy,” for instance, not only presents a history of Taiga’s calligraphic studies and styles, along with an analysis of Taiga’s calligraphic accomplishments, but situates it within the history of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy— a contextualization it admittedly requires, given Taiga’s love of ancient styles and his then-modern experimentation. Sadako Ohki precisely articulates the processes as well as the history and significance of Taiga’s bamboo paintings with calligraphy; her detailed analysis of the process by which they were created is illuminating. Kinoshita’s investigation of Chinese printed books the artists’ studied is a badly needed update of this complicated issue. Jonathan Chaves analyzes and evaluates Taiga’s poetry in Chinese, giving full translations and annotations of sixty-six of his original Chinese poems (found in appendix 1).

Substantive catalogue entries, many of which run to five hundred or more words, are unusually profuse and informative. Full translations are given of all poems and colophons—a daunting task for most scholars given the range of specialized scripts used by these artists—and include not only poems by Taiga and Gyokuran but also texts they and others transcribed onto their paintings. Given Taiga’s interest in Chinese studies, this means that the book provides an invaluable introduction to Chinese literati classics unfamiliar to scholars who are not Chinese literature specialists, such as the (1083) Ode to a Heavenly Horse by Mi Fu, and An Account of the Garden for Solitary Pleasure (1073) by Sima Guang (Familiar old chestnuts such as the Red Cliff and Peach Blossom Spring are not translated, however.) Facsimiles of seventy-eight of Taiga’s and eleven of Gyokuran’s seals (always a difficult matter with such prolific artists) are found in appendix 2.

There are 208 color entries of Taiga’s and Gyokuran’s work, completely depicted in the catalogue—each panel of the many pairs of screens, each leaf in the case of albums such as Leisurely Places Beyond Ordinary Life, and the full length of a number of long handscrolls. Overall there are more than 420 illustrations. Sixty-six additional photographs of supportive materials, nearly all in color, show portraits of Taiga and Gyokuran and of works by the two, their friends and teachers, along with earlier artistic prototypes. Fourteen full-page color details introduce chapters and exhibition divisions.

Given the immensity of the accomplishments, any criticism is mere cavil. Still, a subject index would have been extremely useful, given that of necessity many subjects are treated in several chapters or catalogue entries. At the very least, inclusion in the index of names of the titles of paintings would have been appreciated, given the size of this catalogue, especially for those of us who want to use it as a text, and for scholars who are trying to sort out the complexities of dating or stylistic development. (Discussion of the dating of Gyokuran’s paintings, for instance, is found both in the chapter on her, especially pages 45–6 and 48, and throughout the catalogue entries. Placement of these discussions makes sense, but it is hard to find what one wants.) Finally, thorny as these issues are, it would have been nice to have the authors’ assistance in sorting out the issues of forgery and authenticity, upon which Fischer and Kinoshita must now be experts. A few hints are given here and there, along with reasons for excluding a few quite anomalous works. Despite these minor flaws, the catalogue is not only a major contribution to scholarship on literati and Japanese art history, but a delight to read and study.

Mara Miller

independent scholar